Economy was not enough, stupid

Authoritarian economics is more complicated than inflation numbers. Erdogan proved this.

There is a famous quote in Turkish politics, delivered by one of the historical oratory geniuses of our country, the late President Suleyman Demirel: “Every government can be brought down by the pan in the kitchen.” It’s simply a fancier way of saying “It’s the economy, stupid”. Well, politics can be more complicated than that and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan proved this last weekend.

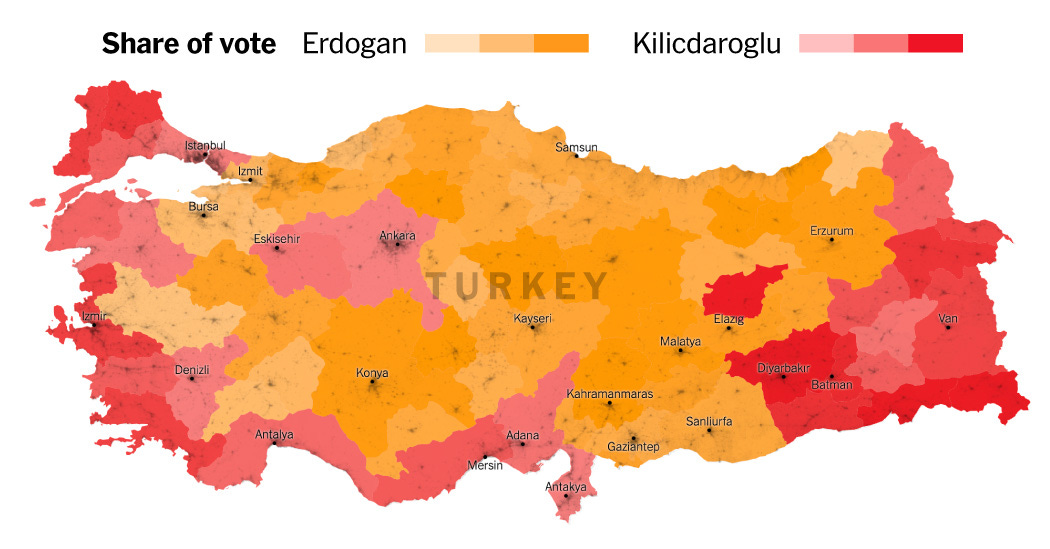

If the economy was enough to bring down a Government, we would’ve seen a landslide. Rather, Erdogan won a majority in Parliament and received 49.5% of the vote. He will probably win the second round comfortably — and depending on the margin, he might annihilate the opposing public’s resilience for the first time.

Turkey’s economic foes are not difficult to spot. Inflation is out of control with independent researchers claiming it’s above 120% annually. The majority of the population claims that they don’t trust Government data and feel inflation is much higher than their numbers. Those that trust the numbers are simply over-politicized and partisan fanatics. (This also reveals that the Turkish people are not simply ‘brainwashed’ by ‘fake news’ — a claim over-relied on by the opposition.)

The Turkish Lira lost 45% of its value against the Dollar only in the last year. If you count the past three years, the meltdown tripled, which also drove inflation as Turkey’s market and manufacturing are highly dependent on international suppliers.

Erdogan’s central bank, which lost its independence completely with the appointment of its latest Governor in March 2021, also followed “unorthodox” policies to (not) combat inflation and the TL’s value: It lowered interest rates as inflation rose. This was worrying for international investors and observers as it risked creating an inflationary shock, which also triggered a further decrease in TL’s value. To break the spiral, the Central Bank started selling its Dollar reserves, making public banks sell them too to keep the TL stable.

Consequentially, the prices of everything went through the roof. Food, housing, textiles, construction materials, stationary, and -yes- pans too! Naturally, rising prices mean lower living standards for the poor. Those that earn just-enough monthly pay to sustain their lives, blue and white collar workers, realized that they are literally working class if the Government isn’t protecting their interests. Now, capital owners earn around 47% of Turkey’s annual GDP and workers only receive 23.7% — increasing inequality.

We can go on. So, if this is not the “pan in the kitchen” that can “bring down any government”, what the hell is? Should the country default? Should its people starve? Should the banks close down and businesses shoot workers who want their pay?

Well, all the above are very macro datasets and even though they affect ordinary people whether the government wants to or not, the devils are in the details.

Trust, trust, trust

Let’s put the first obvious hurdle out in the open. Knowing that the economy is going badly (and blaming the Government for it) does not mean trusting the opposition with fixing the problems. Erdogan’s challenger, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, and his allies —including Erdogan’s former economy czar Ali Babacan, who is very well regarded internationally— failed to build trust. In September 2021, when the economic crisis was much more of the burning topic of the day (data is scarce on this), 45% of the population thought that the opposition wouldn’t be able to fix the economy and 10% said they didn’t know. As months passed, the crisis most probably normalized in people’s minds and the picture must’ve gotten worse.

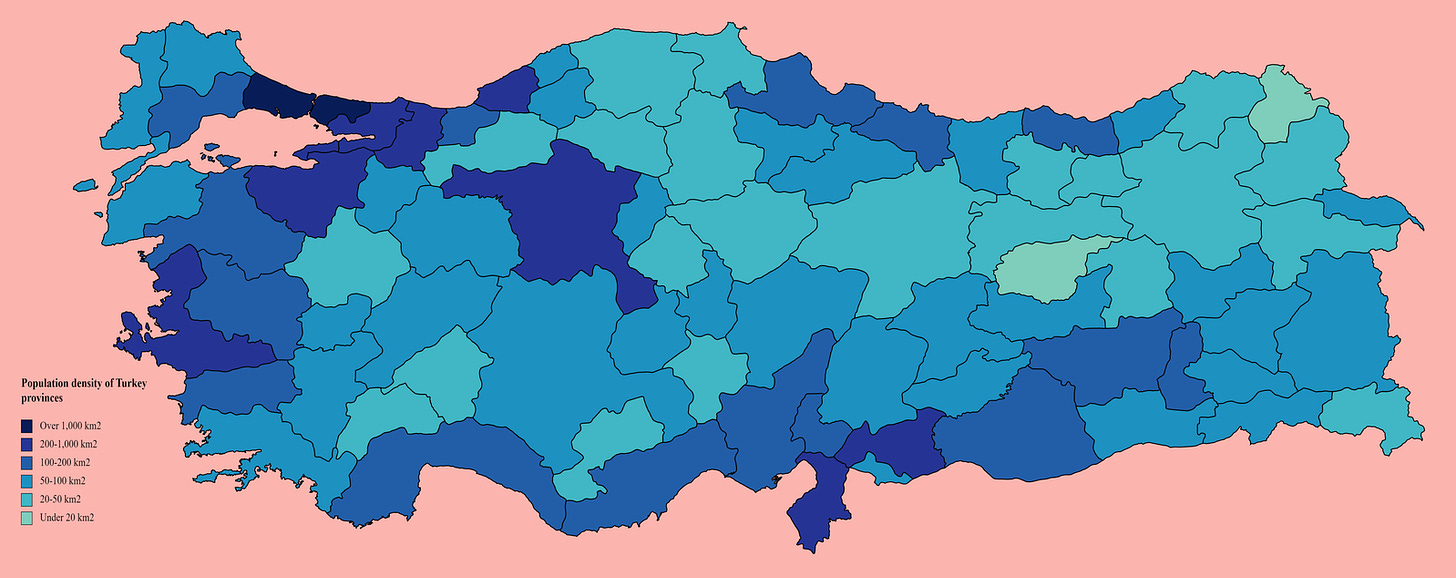

The opposition focused on the macro factors above for too long and failed to make a case for easing citizens’ daily pain. The macro factors are crucial and easily understandable for the big city folk: housing, transportation, and a relative decrease in their pay and living standards are obvious. Unsurprisingly, the opposition performed much better in big cities (this has something to do with societal trust and access to education as well, of course). Erdogan didn’t even attempt to increase his chances on this front during his campaign.

Thank-the-state-economics

What about the Erdogan-backing rural Turkey though? No one is immune to these conditions. The crisis is just too overwhelming. But not everyone’s crisis is equal.

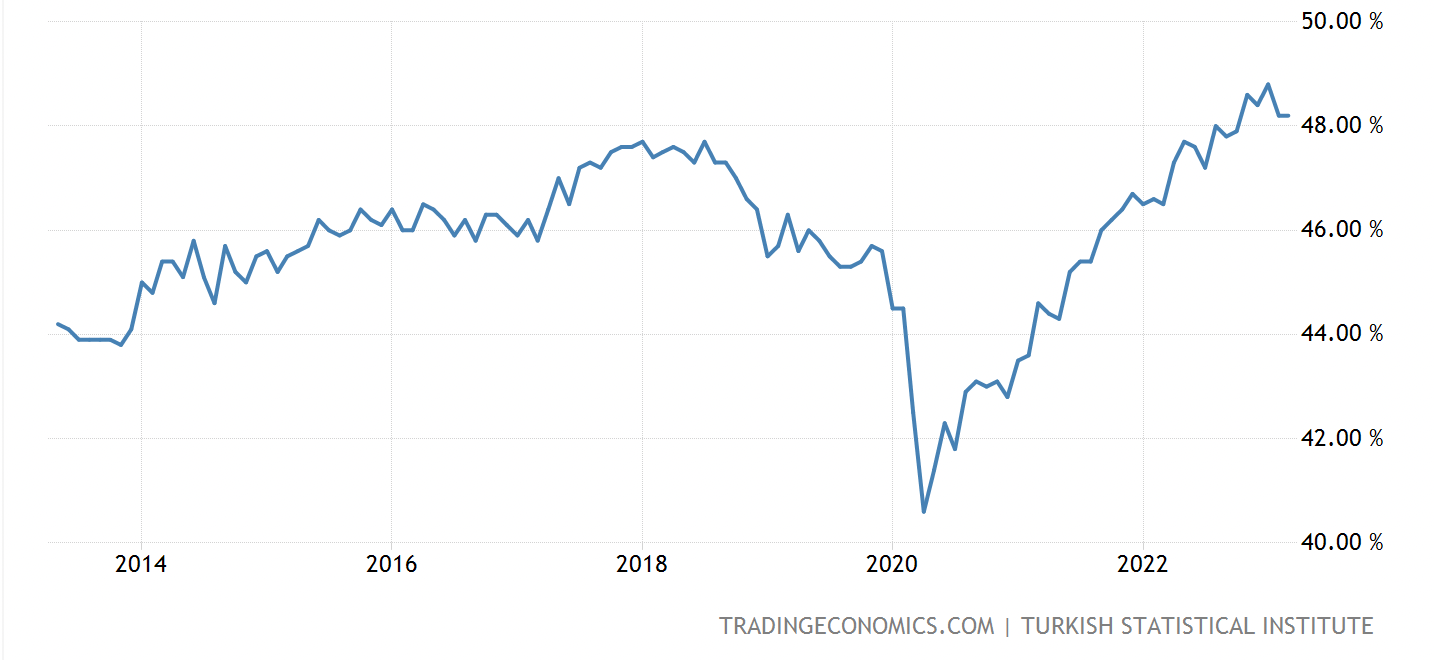

Firstly, although the consequences of the Central Bank’s unorthodox policies are clearly visible to the country’s macroeconomic issues, they —supported by a spending spree by the Government— either created jobs or at least stabilized the job market. According to government statistics (not the most trustworthy source), above 48% of the population is employed at the moment. This number should increase when off-the-books jobs are counted in, which are substantial in the Turkish economy.

This has two implications: One, even though people are employed they are well underpaid especially in big cities due to macroeconomic instability. That’s why wages and job security should’ve been the point of attack for the opposition. It wasn’t. They focused on academic macroeconomic debate rather than this. Second, for the employed people outside big cities, the crisis didn’t create an unemployment spree. These factors can explain why unorthodoxy was reasonable for Erdogan’s political chances (though it can’t explain the failure of policymakers that created the crisis in the beginning).

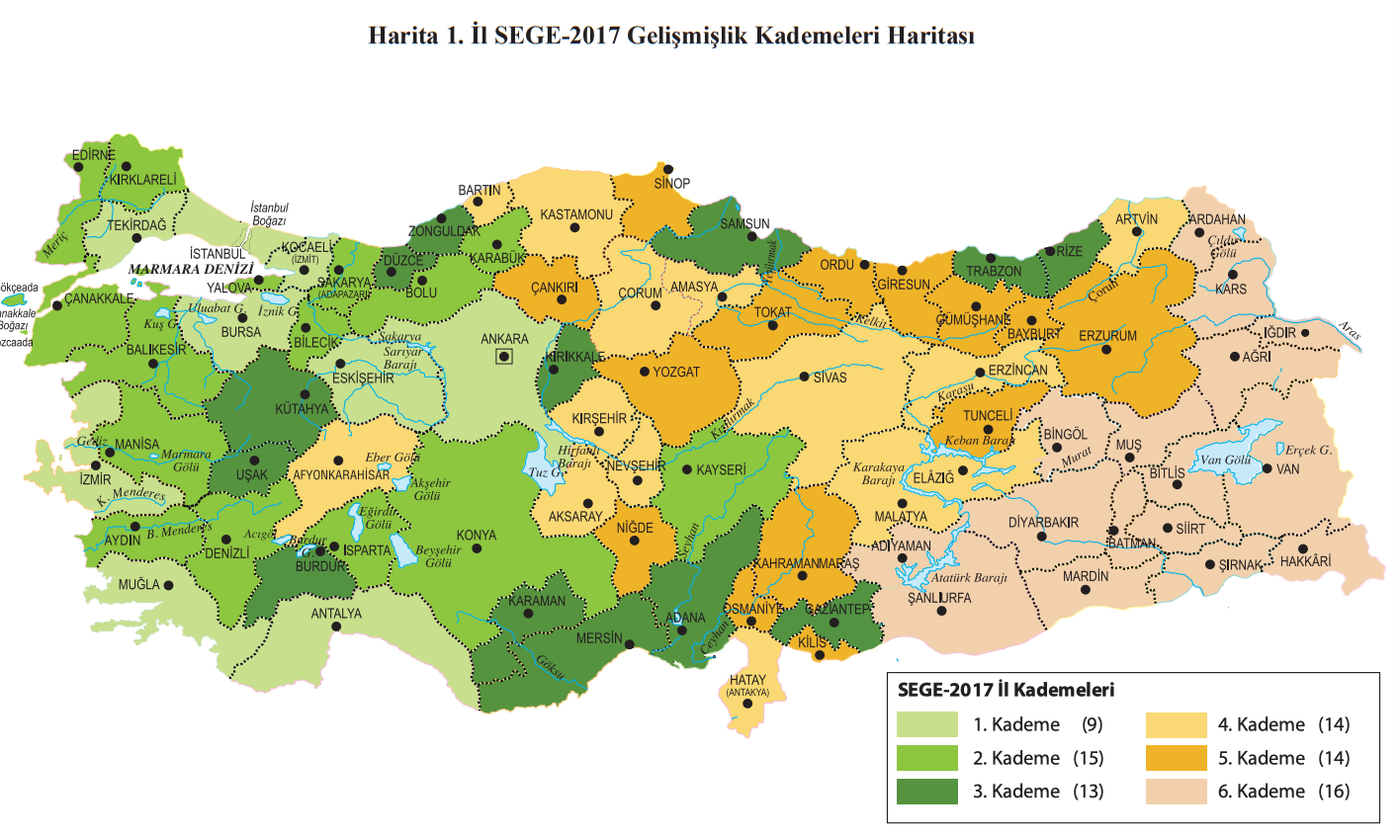

Secondly, the prices —especially of housing and locally produced/manufactured goods— should’ve increased relatively less in rural areas compared to bigger cities. Easy: these places are not receiving large sums of immigrants —rather they are giving them away—, have a less dense population, enough housing and not much of any strict development regulations, and produce their goods locally. They are economically less advanced but since they are less dependent on national/international markets, they are more resilient to outer shocks.

Thirdly, these areas have a lower economic development rate than dense cities. This doesn’t simply mean that they have lower life standards or wages — it also reveals that they are more dependent on state/crony investment and jobs. As you can see in the Government’s economic development index below, the less dense a place, the less developed it is and the more likely to vote for Erdogan as well. (Don’t count the Kurdish towns in the North East region. That’s a different story as identities and other political actors play their parts.)

That’s why in these regions resolving the economic crisis rests on lowering risks of unemployment and austerity, and their economies depend on continued investment. Thus promises of revolutionary economic changes (‘I will annihilate Erdogan’s crony businesses’ was Kilicdaroglu’s main economic promise) and macroeconomic talk are difficult to resonate in these areas. However, significant rises in the minimum wage and increases in state help or subsidies are definitely popular policies — and these are the policies Erdogan implemented. Although the minimum wage cannot provide any meaningful income to a professional in Istanbul, it means much more to someone in underdeveloped Anatolian cities. They looked for help through tough times and stability. Change was too risky.

Additionally, these voters probably faced status anxiety and found resolve in the Government’s policies and Erdogan’s leadership. Their economic fortunes grew under Erdogan’s rule over the past two decades. These deprived cities formed their own middle classes thanks to new investments and housing opportunities. The direct consequence of the economic crisis should’ve stoked status anxiety among them. However, the Government’s interventions in the market and funded subsidies calmed this anxiety and hence rose the consumer confidence index (more on this below). That’s why putting trust in the Government as the country goes through an economic crisis became a rational (or at least rationalized) stance for them.

That’s probably why Erdogan retained his support in rural Turkey. The economic situation did not cause major shifts in his strongholds not because these people are “brainwashed” but because Erdogan’s seemingly irrational economic policies were rational politically for them. He chose not to fight the economic crisis with traditional tools and policies because the political pill could’ve been too distasteful to swallow.

Implementing policies specifically designed to retain support is not Erdogan’s invention. It’s straight out of the populist authoritarianism’s toolkit. It’s mostly a long-term project for autocrat-wannabes.

Bryn Rosenfeld, in his great book, The Autocratic Middle Class, shows that middle classes that are built on state funds or enterprises (we can add ‘crony businesses’ here to understand the Turkish case) become so dependent on the state in maintaining their socio-economic status, that they get autocratic as well:

A middle class whose status depends on public employment for an authoritarian state is often antithetical to democracy. (…) The economic institutions of state employment benefit autocrats, helping them to secure the support of key middle-class constituencies. (…)

The middle classes are stakeholders in existing autocratic systems. (Emphasis mine.)

Rosenfeld uses examples of post-Soviet states and -of course- Russia to show this. As people’s statuses get more dependent on the state, less likely they are to support democratic movements. For generations, political thinkers thought that a growing middle class was the ultimate way to reach democratization. As economies grew more and more complex and as crony capitalism gathered incredible sums of money, this understanding of the ‘middle class’ proved to be superficial. Dependency disincentivizes democratic progress.

A similar scenario seems to be in place for Erdogan’s strongholds in Turkey. ‘Thank-the-state’ citizens voted for the stability of status for themselves.

Good timing

Lastly, Erdogan timed this election perfectly as well. Yes, we are still talking about economics.

Obviously, the mentioned crisis factors are far from zeroed out. (Some will get much worse, very quickly.) However, neither inflation nor TL’s value is a great indicator of voting behaviour. Using economic growth is quite difficult in this election too since growth is shared very unequally at this point.

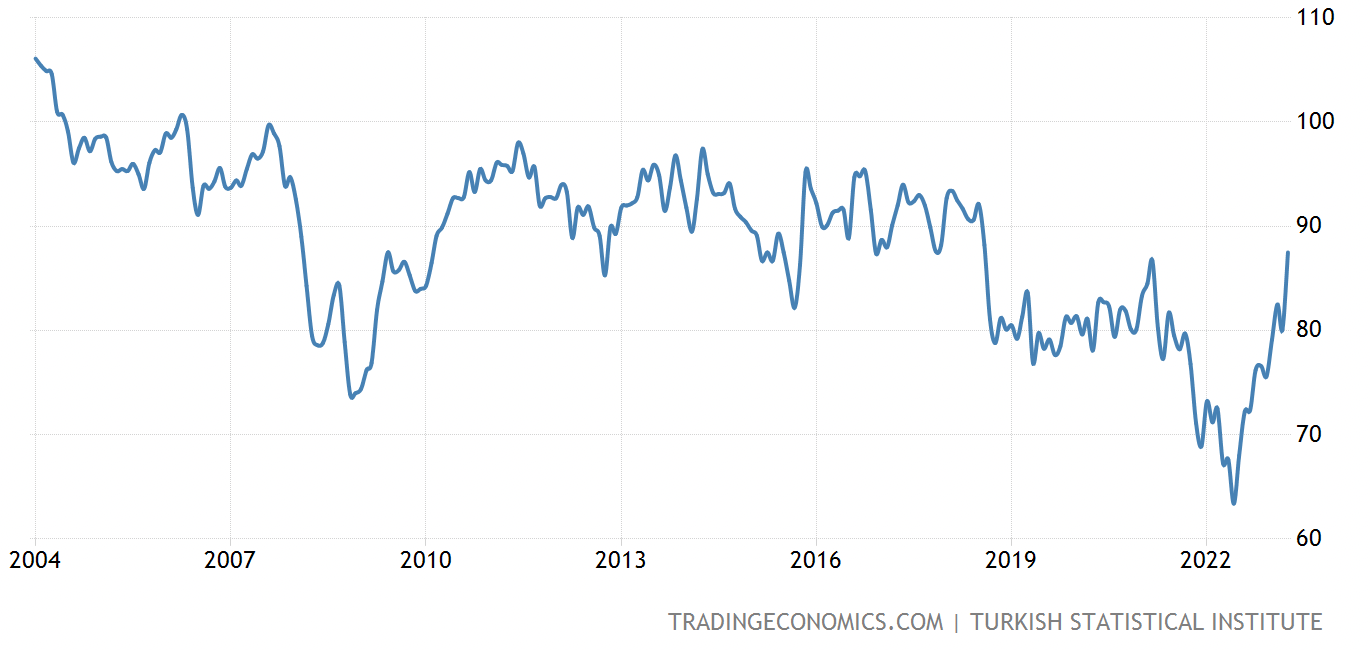

But the consumer confidence index, which is an indication of future developments of households’ consumption and saving, based upon their expected financial situation, their sentiment about the general economic situation, unemployment and capability of savings, has mostly been a good indicator of incumbent popularity in Turkey. The higher the consumer trust gets, the more popular the Government becomes. (But, according to Ceyhan Erener, it’s not a good indicator of a challenger’s vote capacity.)

Historically, this has been quite consistent:

In the study, a positive and significant relationship was found between the vote of the [Erdogan’s] Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the consumer confidence index. A one-unit increase in the consumer confidence index results in a 44-unit increase in AK Party votes.

For instance, in March 2019, when the last local elections took place, the consumer confidence index was at a historic low, 81.1, and Erdogan famously lost most of the big cities. Next month he -once again- lost Istanbul.

Similarly, during the summer of 2015, the consumer confidence index was on a negative trend and Erdogan’s AKP lost its parliamentary majority in the June elections. As the index picked up pace, AKP’s popularity also increased and won its majority back in November 2015.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that the index is the single indicator of Erdogan’s votes. Far from it. Many other political, personal, and security-based concerns play their share of roles but they also shape the index since it doesn’t only rest on macroeconomic data. It’s not a coincidence that Erdogan picked this month for the election. After months of historic lows (under March 2019 even), the consumer confidence index once again is on a positive trajectory. Some of this probably comes from the fact that the consumers were expecting the election but the positive trend started before the electoral cycle. It seems that the Government’s spending spree has worked in rebuilding trust in the economy for the citizens, at least.

Wasted opportunity

The opposition could’ve (and should’ve) used the ongoing economic meltdown to their advantage. They had world-beating economists like Bilge Yilmaz, Umit Ozlale, Ali Babacan, and Selin Sayek Boke in their teams. Especially the Iyi Party’s economic policies, crafted by Yilmaz, were well suited for the moment with a focus on austerity for the rich and continued development for the lower/middle classes. What they lacked was harmony. Their presidential candidate, Kilicdaroglu, stoked intra-alliance debates (who will manage the economy?) by only highlighting Babacan’s possible role in his Government and refused to give space to Iyi Party’s policies and actors. The outcome was a messy and ineffective message on the economy, which did not resonate with rural Turkey. The democratic opposition wasted a historic opportunity. Poor alliance management and the hegemony of day-to-day, gossipy politics damaged their credibility.

Well, as we have seen economics can explain many -if not all- trends in societal behaviour. So, yes, it’s still the economy, stupid. However, looking at the most obvious of all data points —like inflation or currency— sometimes cannot be enough to understand the domestic dynamics of a country — especially if it’s a crony autocracy with a populist leader. Even in the worst of times, with the right targeted policies in place, leaders can protect their vote base from the forces of economic voting. Erdogan performed a great example of this last weekend. The opposition played right into his hand.

PS: If you found this article insightful and want similar content delivered to you on international politics, please subscribe (and pay for it if you can) and share it with friends.

What is the Portillo Moment?

Politics is losing touch. Not simply with ordinary people but also with sensible and rational thinking. Partisan hacks, ideological newspapers, biased networks, short-term-and-media-obsessed politics, and social echo chambers are not helping.

Things need to change if things are to get better. We should seek sensibility in politics. This is what this blog will try to do with every post.

The Portillo Moment of 1997, when a leading British Conservative politician lost his safe seat to New Labour, represents a historic moment that sensible politics claimed its throne. After almost two decades out of power, this was Labour’s landslide that came only after the party made peace with sensibility. Michael Portillo was not a radical but even he couldn’t resist that political wave.

The sea change in politics was so powerful that when Portillo returned to Parliament a few years later and became the Shadow Chancellor, he spent most of his time explaining why Conservatives had to accept many of Labour’s policies. This is the consequence of ‘what works’, sensible politics. It builds a new centre.

I believe that anti-radical politics need a similar moment desperately all over the world and this blog is written from that perspective. Believe me, it’s difficult to find sensible voices these days.

Subscribe if this is of interest to you (pay if you can, as I am doing this all by myself) and share with others who may be interested as well.